I have now completed two chunks of reflecting on my own hermeneutical autobiography. I'll at least continue through this third chunk. The two previous ones were:

1. Learning to read in context and

2. Determining the original text

In the first group of posts, I talked about my earliest realizations about what it means to read the Bible in its literary and historical context. In the second, I talked about my early struggles with questions of manuscripts and the original text. This group has to do with the way the NT reads the OT.

_______________

When I was in college, Dr. Marling Elliott was, at least in retrospect, a very influential teacher for me. His classes moved at a turtle's pace, mind you. He had little set agenda. The class could easily set an agenda for him. Every once and a while he would stop and ask, "Are we doing any good here?" Every class was like a Rogerian counseling session.

But he was incredibly intelligent and he did a good job of raising questions. He was completely non-directive. He mainly wanted to facilitate our own processing of issues. Who knows what he actually thought about them.

I applied the fundamentalism of my pre-college years to his classes as well. At one point I wrote a paper trying to reconcile the gospel accounts of Peter's denial historically, for example. If I move on to a fourth chunk of reflections, I'll return to it. In this chunk, I remember him in a Gospels class raising the question of how Matthew was using the Old Testament when it quoted Hosea 11:1.

Matthew quotes this verse and says that Joseph, Mary, and Jesus stayed in Egypt until the death of Herod the Great, "in order that it might be fulfilled that which was spoken by the Lord through the prophet, saying, 'Out of Egypt I called my Son.'" I was well acquainted with the page at the back of my Thompson Chain Reference KJV that had a chart of all the prophecies from the OT that Jesus had fulfilled. I just had never actually gone back to read any of those passages in context.

Dr. Elliott took us back to Hosea 11:1-2 and we read it, "When Israel was a child, I loved him, and out of Egypt I called my son, but the more they were called, the more they went away. They sacrificed to the Baals and burnt offerings to idols." It sure didn't seem to be about Jesus. In fact, it wasn't even a prophecy. It was talking about the past, about the exodus. What was Matthew thinking?

At the time, I always smiled when things like this one came up. I was confident there was an answer and that I could figure it out. If Dr. Elliott gave an answer, I don't remember it. My thoughts always wandered like a fly buzzing around the room, only occasionally knocking into the professor... and perhaps occasionally dozing in some corner.

At the end of my first year of seminary, though, I still had no answer. It was troubling me greatly. Was God asking me to make an irrational leap of faith? Was it a test? Would God ask me to force myself to believe a lie to show my submission to him?

This was the issue that I brought to my pastor at home in the summer, the one where he suggested perhaps the original manuscript of Hosea or Matthew read something different. It was a nice try, but there are no textual variants in relation to these passages. At the time I tied the question to inerrancy, which I don't now. I assumed that the question was whether Matthew was right or wrong about the meaning of Hosea.

I now believe that it is rather the fundamentalist approach to Scripture that is wrong and that it was perfectly appropriate for Matthew to read Hosea in a figurative way like other Jewish exegetes of his day...

Saturday, June 30, 2012

Thursday, June 28, 2012

In the News...

A number of things in the news of some significance.

First, a German court ruled that parents could not circumcise their children because of the potential bodily harm without the consent of the child. It is unclear to me what real effect this ruling actually will have in the German legal system, but it reflects the perennial struggle between religious freedom and government as an arbiter of individual rights. Do Jewish and Muslim parents have the right to have their children circumcised when a child is too young to have a say in the decision? The potential religious consequences of this discussion are staggering.

It reminds us of recent debates over whether a public catholic institution must provide insurance to its employees that involves contraception or previous decisions about providing life-saving intravenous blood transfusions to children of Seventh Day Adventists. Or can a photographer refuse to shoot a gay wedding on the basis of religious principle? I do suspect that we will do better in the future if we focus on rights to follow our own religious beliefs rather than expending our energies trying to force the rest of America to follow our religious beliefs.

Second, there was the recent decision of the Obama administration not to deport individuals who would otherwise have been able to stay in the country if the Dream Act had passed. It's clearly a political move on Obama's part in light of the coming election, but it is also clearly something he believes in and tried to get passed earlier.

Finally, there were the Supreme Court rulings on Obamacare today. I am not expert enough to know whether the health care law will be beneficial or not. One thing is sure, there is no such thing as complete objectivity. I would like to think that Supreme Court justices are more objective than the vast majority of people. But they regularly disappoint what "both sides" think is objective. ;-)

First, a German court ruled that parents could not circumcise their children because of the potential bodily harm without the consent of the child. It is unclear to me what real effect this ruling actually will have in the German legal system, but it reflects the perennial struggle between religious freedom and government as an arbiter of individual rights. Do Jewish and Muslim parents have the right to have their children circumcised when a child is too young to have a say in the decision? The potential religious consequences of this discussion are staggering.

It reminds us of recent debates over whether a public catholic institution must provide insurance to its employees that involves contraception or previous decisions about providing life-saving intravenous blood transfusions to children of Seventh Day Adventists. Or can a photographer refuse to shoot a gay wedding on the basis of religious principle? I do suspect that we will do better in the future if we focus on rights to follow our own religious beliefs rather than expending our energies trying to force the rest of America to follow our religious beliefs.

Second, there was the recent decision of the Obama administration not to deport individuals who would otherwise have been able to stay in the country if the Dream Act had passed. It's clearly a political move on Obama's part in light of the coming election, but it is also clearly something he believes in and tried to get passed earlier.

Finally, there were the Supreme Court rulings on Obamacare today. I am not expert enough to know whether the health care law will be beneficial or not. One thing is sure, there is no such thing as complete objectivity. I would like to think that Supreme Court justices are more objective than the vast majority of people. But they regularly disappoint what "both sides" think is objective. ;-)

Wednesday, June 27, 2012

The Four Fold Sense of Scripture

Excellent piece on this found here, by the way.

By the time of the Middle Ages, Christian interpreters of the Bible had come to classify the interpretation of Scripture in terms of four "senses" that the biblical text could have. The default would be to take a biblical text literally, the "literal sense." We might say today that the literal sense of a text is when the words are taken in their normal way.

As a side note, the English use of the word "literally" has changed to where people often mean something like "really." Take the English idiom, "he went through the roof," which means to suddenly get really angry. Someone might say, "He literally went through the roof," when what they mean is that he really "went through the roof."

This is not what the word "literally" means when we talk about the literal sense of certain words. In fact, to literally go through the roof in this context would mean to take the words in their normal sense, meaning that a person's body passed through the physical structure of the roof above one's head. The literal sense of a text is thus the meaning it most naturally had at the time and place it was written, the meaning its author and audience would most likely have assigned the words at the time of writing.

Mind you, medieval interpreters were not well equipped to distinguish between what the normal sense of words would have been for the authors of the Bible and what seemed to be the normal sense of the words to them as readers. To approach the normal sense of words in the Bible in their original terms, we have to know how the people at the time of writing were using the words. Such meanings were functions of the socio-cultural worlds in which the authors and audiences of the biblical texts lived, and we do not always have clear access to such "deep structures" behind language.

Although the medieval interpreters came to speak of four possible senses to the words of Scripture, they really only boiled down to two categories--literal and non-literal. Either you read the words for what they normally mean or you read them in some other, non-literal way. So one of the four senses of Scripture is the literal, and the other three are all non-literal ways of reading Scripture.

The three non-literal or "spiritual" ways of reading Scripture are the 1) allegorical, 2) moral, and 3) anagogical. The allegorical sense sees a teaching or truth in the text by taking the words in something other than their normal sense. The moral sense sees ethical instruction about how to live by taking the words in something other than their normal sense. The anagogical or future sense sees teaching about what is still to come, including heaven or the afterlife, by taking the words in something other than their normal sense.

Lest we dismiss these sorts of readings out of hand too quickly, it is important to recognize that the New Testament authors interpreted the Old Testament in all these ways. Further, many Christian teachers today use these sorts of methods without realizing it, especially prophecy teachers. In Galatians 4:21-31, Paul makes an allegory out of the Genesis story of Hagar and Sarah. In 1 Corinthians 9:9-10, Paul interprets the Deuteronomy command not to muzzle the ox while treading the grain morally, concluding that the real meaning of the command has to do with materially supporting those who do ministry work. And Hebrews 4:8 arguably read Psalm 40 anagogically when it took the "rest of God" to refer to something future rather than the entrance of Israel into Canaan.

The Protestant Reformation seriously questioned the use of allegory in interpretation. Allegory is when the elements of a biblical text are made to correspond to truths that were not part of the original meaning. The classic example comes from Augustine's allegorical interpretation of the Parable of the Good Samaritan. The man who is mugged is Adam, who is mugged by the Devil and his angels. The priest and Levite are the Law, which cannot provide salvation. Christ is the Good Samaritan and the inn is the church. Obviously none of these meanings were originally part of Luke 10.

In the early 1500s, Martin Luther wished to get back to the teachings of the Bible and prune back the accretions of the Middle Ages. But if Scripture could be taken allegorically, there was nothing to stop the Roman Catholic Church from claiming that its later teachings were simply the appropriate spiritual interpretations of the Bible. It was thus somewhat inevitable that the drive back to "Scripture alone" (sola scriptura) would emphasize literal interpretation over "spiritual" interpretation.

But this trajectory introduced a two-fold problem for Protestant interpreters. First, there is the problem, as we have seen, that the New Testament texts themselves at times use allegorical methods. The second problem is that the first centuries of the church are arguably central for core Christian understanding, since it was in the 300s and 400s that our current beliefs about the Trinity and the divinity of Christ were really hammered out in detail. One might argue that "spiritual" interpretation played a role in the formation of these core Christian beliefs.

To address the first problem, Protestant interpreters developed a category called "typology," which they distinguished from allegory, even though this distinction was unknown to the ancients. Typology supposedly was when a New Testament author took an Old Testament passage in a non-literal way but in a way that built on some truth that was intrinsic to the Old Testament passage itself on its own terms. So when Hebrews warns its audience to continue in faith until Christ returns and contrasts the Israelites who did not enter God's rest in Canaan, the correspondence is very analogous.

The moral or tropological sense finds some ethical instruction by taking some passage in a figurative sense. When non-literal interpretation is divided in this way, allegory comes to apply more to finding teaching in a text and the moral sense has to do with finding ethics in a text that was not straightforwardly ethical in that way before. Paul's thus finds an ethic about supporting ministers in instruction that was literally about oxen.

One might suggest that the bulk of dispensational prophecy teaching about the future, from its rise in the 1800s under John Darby to its most recent manifestations with individuals like Tim LaHaye, is a variety of anagogical or futurist interpretation. Few of the texts such schools of prophecy use are actually read in context. So Mark 13, which so clearly relates to the destruction of the temple in AD70 is taken to prophesy a temple that is yet to be rebuilt.

The aversion of Protestantism to allegory led to an important distinction that we should keep in mind in any future discussions. Although there is still often resistance to the existence of allegory in the biblical texts, it is clear that not everything in the Bible is literal. A parable, for example, is meant to be interpreted symbolically at least to some extent. When Jesus says the kingdom of God "is like" something, he is using simile.

It is thus better to distinguish between the "plain sense" of the Bible and spiritual or a "fuller sense" (sensus plenior) to a text than to distinguish between literal and non-literal. The plain sense of a text is its original sense, whether it was originally meant to be taken literally or originally meant to be taken as a metaphor, allegory, etc. The question then becomes whether it is appropriate for us to allegorize the text in ways that were not originally intended.

By the time of the Middle Ages, Christian interpreters of the Bible had come to classify the interpretation of Scripture in terms of four "senses" that the biblical text could have. The default would be to take a biblical text literally, the "literal sense." We might say today that the literal sense of a text is when the words are taken in their normal way.

As a side note, the English use of the word "literally" has changed to where people often mean something like "really." Take the English idiom, "he went through the roof," which means to suddenly get really angry. Someone might say, "He literally went through the roof," when what they mean is that he really "went through the roof."

This is not what the word "literally" means when we talk about the literal sense of certain words. In fact, to literally go through the roof in this context would mean to take the words in their normal sense, meaning that a person's body passed through the physical structure of the roof above one's head. The literal sense of a text is thus the meaning it most naturally had at the time and place it was written, the meaning its author and audience would most likely have assigned the words at the time of writing.

Mind you, medieval interpreters were not well equipped to distinguish between what the normal sense of words would have been for the authors of the Bible and what seemed to be the normal sense of the words to them as readers. To approach the normal sense of words in the Bible in their original terms, we have to know how the people at the time of writing were using the words. Such meanings were functions of the socio-cultural worlds in which the authors and audiences of the biblical texts lived, and we do not always have clear access to such "deep structures" behind language.

Although the medieval interpreters came to speak of four possible senses to the words of Scripture, they really only boiled down to two categories--literal and non-literal. Either you read the words for what they normally mean or you read them in some other, non-literal way. So one of the four senses of Scripture is the literal, and the other three are all non-literal ways of reading Scripture.

The three non-literal or "spiritual" ways of reading Scripture are the 1) allegorical, 2) moral, and 3) anagogical. The allegorical sense sees a teaching or truth in the text by taking the words in something other than their normal sense. The moral sense sees ethical instruction about how to live by taking the words in something other than their normal sense. The anagogical or future sense sees teaching about what is still to come, including heaven or the afterlife, by taking the words in something other than their normal sense.

Lest we dismiss these sorts of readings out of hand too quickly, it is important to recognize that the New Testament authors interpreted the Old Testament in all these ways. Further, many Christian teachers today use these sorts of methods without realizing it, especially prophecy teachers. In Galatians 4:21-31, Paul makes an allegory out of the Genesis story of Hagar and Sarah. In 1 Corinthians 9:9-10, Paul interprets the Deuteronomy command not to muzzle the ox while treading the grain morally, concluding that the real meaning of the command has to do with materially supporting those who do ministry work. And Hebrews 4:8 arguably read Psalm 40 anagogically when it took the "rest of God" to refer to something future rather than the entrance of Israel into Canaan.

The Protestant Reformation seriously questioned the use of allegory in interpretation. Allegory is when the elements of a biblical text are made to correspond to truths that were not part of the original meaning. The classic example comes from Augustine's allegorical interpretation of the Parable of the Good Samaritan. The man who is mugged is Adam, who is mugged by the Devil and his angels. The priest and Levite are the Law, which cannot provide salvation. Christ is the Good Samaritan and the inn is the church. Obviously none of these meanings were originally part of Luke 10.

In the early 1500s, Martin Luther wished to get back to the teachings of the Bible and prune back the accretions of the Middle Ages. But if Scripture could be taken allegorically, there was nothing to stop the Roman Catholic Church from claiming that its later teachings were simply the appropriate spiritual interpretations of the Bible. It was thus somewhat inevitable that the drive back to "Scripture alone" (sola scriptura) would emphasize literal interpretation over "spiritual" interpretation.

But this trajectory introduced a two-fold problem for Protestant interpreters. First, there is the problem, as we have seen, that the New Testament texts themselves at times use allegorical methods. The second problem is that the first centuries of the church are arguably central for core Christian understanding, since it was in the 300s and 400s that our current beliefs about the Trinity and the divinity of Christ were really hammered out in detail. One might argue that "spiritual" interpretation played a role in the formation of these core Christian beliefs.

To address the first problem, Protestant interpreters developed a category called "typology," which they distinguished from allegory, even though this distinction was unknown to the ancients. Typology supposedly was when a New Testament author took an Old Testament passage in a non-literal way but in a way that built on some truth that was intrinsic to the Old Testament passage itself on its own terms. So when Hebrews warns its audience to continue in faith until Christ returns and contrasts the Israelites who did not enter God's rest in Canaan, the correspondence is very analogous.

The moral or tropological sense finds some ethical instruction by taking some passage in a figurative sense. When non-literal interpretation is divided in this way, allegory comes to apply more to finding teaching in a text and the moral sense has to do with finding ethics in a text that was not straightforwardly ethical in that way before. Paul's thus finds an ethic about supporting ministers in instruction that was literally about oxen.

One might suggest that the bulk of dispensational prophecy teaching about the future, from its rise in the 1800s under John Darby to its most recent manifestations with individuals like Tim LaHaye, is a variety of anagogical or futurist interpretation. Few of the texts such schools of prophecy use are actually read in context. So Mark 13, which so clearly relates to the destruction of the temple in AD70 is taken to prophesy a temple that is yet to be rebuilt.

The aversion of Protestantism to allegory led to an important distinction that we should keep in mind in any future discussions. Although there is still often resistance to the existence of allegory in the biblical texts, it is clear that not everything in the Bible is literal. A parable, for example, is meant to be interpreted symbolically at least to some extent. When Jesus says the kingdom of God "is like" something, he is using simile.

It is thus better to distinguish between the "plain sense" of the Bible and spiritual or a "fuller sense" (sensus plenior) to a text than to distinguish between literal and non-literal. The plain sense of a text is its original sense, whether it was originally meant to be taken literally or originally meant to be taken as a metaphor, allegory, etc. The question then becomes whether it is appropriate for us to allegorize the text in ways that were not originally intended.

If I were to found a university...

When we went about designing a seminary, we started with the knowledge, skills, and dispositions we believed a pastor should have and worked backward to the curriculum. This is not the traditional way of doing education. The traditional way is to have a set of standard courses that correspond to classical subjects that have been around in some form or another since ancient times. You start with the trivium of grammar, logic, and rhetoric. Then you add the quadrivium of arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy.

The traditional university potentially faces the same crisis that seminaries have. They are perceived to be irrelevant to what a person actually needs to know with a price tag that can infuriate. Universities do have a major advantage that seminaries don't. Eighteen year olds don't go to college just to get educated. Honestly, it's much more about the social life.

If we were to design a college or university from scratch these days, we would ideally start with what students actually need to know, be able to do, and what attitudes they need to have to do them. Then we would work backward to a curriculum to get them there.

Mind you, the best universities have been back filling their curricula for years. And very targeted disciplines have been required to do these sorts of things to meet state standards and such. If you are studying nursing or education, your field is well sorted.

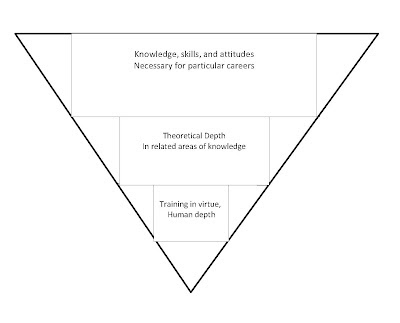

There is the additional problem that a lot of students don't know what they want to do. It is perhaps only natural that colleges tend to start with the bottom part of the triangle above, liberal arts, then go to the top part to train specific skills, while slipping in some theoretical depth for those who want it--or you can get that in graduate school.

Ideally, though, you would know the specific career you wanted to go into from the start and you would first learn the very concrete skills you need to be able to do it well. Then you would add theoretical depth to understand the "inners" of why you do things that way. Finally, you would study what it means to be a virtuous and full human, especially in the context of the life you plan to lead. At a Christian university, this is the place where faith especially comes into play.

What distinguishes a university from a technical school more than anything else is the bottom part of the triangle. Without a sense of history, of culture, of art, of virtue, of the place of science in the world we live, we cannot intelligently participate in the governing of society. The problem is that these areas are often not taught in ways that make their relevance clear, nor are they usually taught in relation to a person's trajectory in life.

If I were founding a university, I'd try to do what we tried to do with the seminary. Focus especially on the skills and knowledge necessary to do the job, while adding as much theoretical depth as possible while still remaining affordable. And in the university setting, you would add the element of "training to be human," the liberal arts, but taught in a way that makes their relevance to life clear.

The traditional university potentially faces the same crisis that seminaries have. They are perceived to be irrelevant to what a person actually needs to know with a price tag that can infuriate. Universities do have a major advantage that seminaries don't. Eighteen year olds don't go to college just to get educated. Honestly, it's much more about the social life.

If we were to design a college or university from scratch these days, we would ideally start with what students actually need to know, be able to do, and what attitudes they need to have to do them. Then we would work backward to a curriculum to get them there.

Mind you, the best universities have been back filling their curricula for years. And very targeted disciplines have been required to do these sorts of things to meet state standards and such. If you are studying nursing or education, your field is well sorted.

There is the additional problem that a lot of students don't know what they want to do. It is perhaps only natural that colleges tend to start with the bottom part of the triangle above, liberal arts, then go to the top part to train specific skills, while slipping in some theoretical depth for those who want it--or you can get that in graduate school.

Ideally, though, you would know the specific career you wanted to go into from the start and you would first learn the very concrete skills you need to be able to do it well. Then you would add theoretical depth to understand the "inners" of why you do things that way. Finally, you would study what it means to be a virtuous and full human, especially in the context of the life you plan to lead. At a Christian university, this is the place where faith especially comes into play.

What distinguishes a university from a technical school more than anything else is the bottom part of the triangle. Without a sense of history, of culture, of art, of virtue, of the place of science in the world we live, we cannot intelligently participate in the governing of society. The problem is that these areas are often not taught in ways that make their relevance clear, nor are they usually taught in relation to a person's trajectory in life.

If I were founding a university, I'd try to do what we tried to do with the seminary. Focus especially on the skills and knowledge necessary to do the job, while adding as much theoretical depth as possible while still remaining affordable. And in the university setting, you would add the element of "training to be human," the liberal arts, but taught in a way that makes their relevance to life clear.

Augustine's On Christian Doctrine (Part 2)

I began this evaluative summary Monday. For the full text of Augustine's On Christian Doctrine, see here.

_________________

Augustine goes on to discuss how to resolve ambiguities of pronunciation or of syllabification (since the words were run together). Some can be resolved by the rule of faith, in other cases one can consult the original Greek.

In chapter 5 of Part 2, Augustine gets into the more difficult question of the metaphorical. He sets down this rule: "We must beware of taking a figurative expression literally." In retrospect, it seems fairly obvious that Augustine often blurred that which was actually intended literally in the biblical text with his figurative or figural interpretations of them. As it were, he adopts a God-like perspective to determine what was figurative and what was literal, rather than following the literary clues of the texts themselves inductively.

So he places much of the Jewish Law into the category of figurative, using the example of opposition to Jesus healing on the Sabbath in chapter 6. The Jewish leaders take the figurative Sabbath law literally. Perhaps he is correct about God's mind here (the problem is always how we can know this), but he is wrong about the texts themselves. Nothing in the Old Testament texts themselves would lead a person to take them figuratively, and even Jesus himself in Mark 2 only claims an exception to the Sabbath law, he does not make an allegory out of it.

The problem, Augustine asserts, is that people mistake the sign, the symbolic cue, for the thing itself to which it points. They mistake the sign for the thing signified. The thing signified is spiritual, and it must be our focus. Jesus and the apostles have handed down very few rites, baptism and communion for example. Augustine considered the spiritual meaning of these fairly obvious.

Chapter 10 then addresses the opposite situation where a person takes a literal form of speech as if it were figurative. Here Augustine sets: down a fundamental rule: "Whatever there is in the word of God that cannot, when taken literally, be referred either to purity of life or soundness of doctrine, you may set down as figurative." What you must take literally in Scripture, therefore, is any instruction relating to the love of God and one's neighbor (purity of life), and you must take literally any teaching relating to the catholic faith (soundness of doctrine). On the negative side, we must take literally any instruction in Scripture that tells us to avoid lust.

So any biblical teaching that seems to ascribe some sinful action to God must be taken figuratively, just as any teaching ascribing holiness to humanity. Augustine also shows some awareness of the importance of context and intention when assessing morality. What is appropriate for one time may not be at another, and the same action can be either virtuous or sinful depending on the intention of the person doing it. Blindness to our own context can also hinder us from seeing points where our own customs are out of sync with love of God and neighbor. Meanwhile, others can fall into a sort of relativism because they are aware of how culture affects what one considers right and wrong.

But the rule to "do to others as you would have them do to you" is universal. It cannot be altered by the customs of one's people. So here is the rule again: "carefully turn over in our minds and meditate upon what we read till an interpretation be found that tends to establish the reign of love. Now, if when taken literally it at once gives a meaning of this kind, the expression is not to be considered figurative" (chap. 15). Or again, "If the sentence is one of command, either forbidding a crime or vice, or enjoining an act of prudence or benevolence, it is not figurative. If, however, it seems to enjoin a crime or vice, or to forbid an act of prudence or benevolence, it is figurative" (chap. 16).

From our standpoint today, we can see that Augustine blurs together interpretation and appropriation. Whether a text is figurative or literal, in the first instance, depends on whether the author was using words in their normal senses for the time and place when he or she was writing, not on whether its content suits our theology. However, we as Christians, on the other hand, rightly make decisions on how to appropriate texts by their relation to the law of love or the rule of faith, both of which we believe are literally instructed and taught in various places in Scripture.

The symbolism of some passages can be clarified by those same symbols elsewhere. So a passage where the symbolic meaning of a shield is unclear can be clarified by another passage where it is. It is also not problematic if a person gives an interpretation to one Scripture that fits with a clear interpretation elsewhere. Once again, Augustine here is reading texts theologically rather than in terms of what they originally meant. The original meaning of a passage is a function of its individual context, not of meanings of other passages written in quite different contexts.

Knowledge of tropes or literary devices helps clarify meaning. These are numerous and learned in school, things like allegory, parable, metaphor, and irony. Augustine ends Book 3 of On Christian Doctrine with seven rules found in the works of someone called Tichonius relating to finding allegorical meanings in Scripture.

_________________

Augustine goes on to discuss how to resolve ambiguities of pronunciation or of syllabification (since the words were run together). Some can be resolved by the rule of faith, in other cases one can consult the original Greek.

In chapter 5 of Part 2, Augustine gets into the more difficult question of the metaphorical. He sets down this rule: "We must beware of taking a figurative expression literally." In retrospect, it seems fairly obvious that Augustine often blurred that which was actually intended literally in the biblical text with his figurative or figural interpretations of them. As it were, he adopts a God-like perspective to determine what was figurative and what was literal, rather than following the literary clues of the texts themselves inductively.

So he places much of the Jewish Law into the category of figurative, using the example of opposition to Jesus healing on the Sabbath in chapter 6. The Jewish leaders take the figurative Sabbath law literally. Perhaps he is correct about God's mind here (the problem is always how we can know this), but he is wrong about the texts themselves. Nothing in the Old Testament texts themselves would lead a person to take them figuratively, and even Jesus himself in Mark 2 only claims an exception to the Sabbath law, he does not make an allegory out of it.

The problem, Augustine asserts, is that people mistake the sign, the symbolic cue, for the thing itself to which it points. They mistake the sign for the thing signified. The thing signified is spiritual, and it must be our focus. Jesus and the apostles have handed down very few rites, baptism and communion for example. Augustine considered the spiritual meaning of these fairly obvious.

Chapter 10 then addresses the opposite situation where a person takes a literal form of speech as if it were figurative. Here Augustine sets: down a fundamental rule: "Whatever there is in the word of God that cannot, when taken literally, be referred either to purity of life or soundness of doctrine, you may set down as figurative." What you must take literally in Scripture, therefore, is any instruction relating to the love of God and one's neighbor (purity of life), and you must take literally any teaching relating to the catholic faith (soundness of doctrine). On the negative side, we must take literally any instruction in Scripture that tells us to avoid lust.

So any biblical teaching that seems to ascribe some sinful action to God must be taken figuratively, just as any teaching ascribing holiness to humanity. Augustine also shows some awareness of the importance of context and intention when assessing morality. What is appropriate for one time may not be at another, and the same action can be either virtuous or sinful depending on the intention of the person doing it. Blindness to our own context can also hinder us from seeing points where our own customs are out of sync with love of God and neighbor. Meanwhile, others can fall into a sort of relativism because they are aware of how culture affects what one considers right and wrong.

But the rule to "do to others as you would have them do to you" is universal. It cannot be altered by the customs of one's people. So here is the rule again: "carefully turn over in our minds and meditate upon what we read till an interpretation be found that tends to establish the reign of love. Now, if when taken literally it at once gives a meaning of this kind, the expression is not to be considered figurative" (chap. 15). Or again, "If the sentence is one of command, either forbidding a crime or vice, or enjoining an act of prudence or benevolence, it is not figurative. If, however, it seems to enjoin a crime or vice, or to forbid an act of prudence or benevolence, it is figurative" (chap. 16).

From our standpoint today, we can see that Augustine blurs together interpretation and appropriation. Whether a text is figurative or literal, in the first instance, depends on whether the author was using words in their normal senses for the time and place when he or she was writing, not on whether its content suits our theology. However, we as Christians, on the other hand, rightly make decisions on how to appropriate texts by their relation to the law of love or the rule of faith, both of which we believe are literally instructed and taught in various places in Scripture.

The symbolism of some passages can be clarified by those same symbols elsewhere. So a passage where the symbolic meaning of a shield is unclear can be clarified by another passage where it is. It is also not problematic if a person gives an interpretation to one Scripture that fits with a clear interpretation elsewhere. Once again, Augustine here is reading texts theologically rather than in terms of what they originally meant. The original meaning of a passage is a function of its individual context, not of meanings of other passages written in quite different contexts.

Knowledge of tropes or literary devices helps clarify meaning. These are numerous and learned in school, things like allegory, parable, metaphor, and irony. Augustine ends Book 3 of On Christian Doctrine with seven rules found in the works of someone called Tichonius relating to finding allegorical meanings in Scripture.

Monday, June 25, 2012

Bob Lyon, Jesus, and Divorce

The Wesleyan Church has, probably, less than ten Bible scholars in its ranks at present. Of course everyone thinks they can speak to the original meaning of the Bible.

I dug up this excerpt on the subject of Jesus and divorce, taken from an article by Bob Lyon, who taught at Asbury until his death. It is in a volume titled, Interpreting God's Word for Today, published by Warner Press in 1982. Its contributors are Bible professors who taught at Wesleyan approved institutions at the time--and therefore while we do not have to agree with Dr. Lyon's train of thought, it stands within the parameters of Wesleyan thought.

I share it to give a sense of how many factors can go into making decisions on these sorts of things.

___________

AN EXAMPLE: THE DIVORCE ISSUE

One example might be given to show the illegitimacy of a nonhistorical approach. The issue of divorce-remarriage adultery is presented in Mark 10:llff.; Matthew 5:32, 19:9; and Luke 16:18. The main problem has to do with Matthew’s exception clauses. Both John Murray and John R. W. Stott resolve the issue dogmatically.[59] Both studies reveal a deep concern for Christian marriage as well as a thorough acquaintance with the background data. Yet both studies are ultimately unsatisfactory because they fail to ask certain necessary historical questions.

How did the varying forms of the saying(s) originate? Is one a derivative of another? Is there a merging of two originally separate topics (divorce and adultery)? Murray regards Matthew 19:9 as “the most pivotal passage” in the New Testament, not because it is the truly authentic (i.e., dominical) statement but because it is the most complete; that is, it has both the exception clause and the remarriage clause.[60] And Stott refers only to the form of the Pharisee’s question found in Matthew.[61] Both presume Mark and Matthew carry the same teaching; Mark omitted the exception clause because he assumed the exception.

But what about the community for whom Mark prepared his Gospel? Did it, or could it, assume an exception? According to Murray, the “silence” of Mark and Luke respecting the right to divorce does not itself prejudice the right to divorce. But are Mark and Luke silent? Did their communities believe they were silent? Do not both Mark and Luke give a rather clear word?

More important, neither Murray nor Stott asks the historical question, "What did Jesus say and how do we explain the various forms of the saying(s)?" From the four texts we come up with the following statements from the lips of Jesus:

(1) Remarriage following divorce constitutes adultery (Mark 10:11ff.; Luke 16:18);

(2) Except in a case of porneia, remarriage following divorce constitutes adultery (Matt. 19:9);

(3) Whoever marries a divorced woman commits adultery (Luke 16:18; Matt. 5:32);

(4) Whoever divorces his wife causes her to commit adultery.

Murray, whose treatment of the texts is much more extended that Stott’s, never asks if these are all separate sayings of Jesus or different versions of a single saying in response to the Pharisees. More important, perhaps, he does not treat the question whether the sayings have anything to do directly with the question the Pharisees asked. In this connection two observations are crucial:

(1) these sayings all relate to the question of adultery and not directly to divorce-that is, they answer the question of what constitutes adultery;

(2) except for Matthew 19:9, none of the sayings in their present context are spoken to the Pharisees who asked the question.

In terms of a historical-rather than dogmatic-approach, it seems Jesus answers the question of the Pharisees solely on the basis of Genesis 1 and 2, and that the various sayings derive from another context involving a discussion of the commandments. Whether they represent separate sayings or variant forms of a single saying is another matter deserving further study. The dogmatic approach fails methodologically because it begins by assuming Matthew and Mark say the same thing. One may come to that conclusion, but one cannot begin there.

Also, Mark and Luke are not, as Murray contends,[62] silent concerning any grounds for divorce. What they say would have to be considered by any common standards of literary analysis to be both clear and unequivocal. It is as arbitrary to interpret Mark and Luke on the basis of Matthew as the reverse. The evangelists must be heard and their community traditions recognized in their own right.

The problematic element in Murray’s study is seen in his variant conclusions. On the one hand, he rightly perceives that in the mind of Jesus, divorce “could not be contemplated otherwise than as a radical breach of the divine institution."[63] Yet elsewhere he says that Jesus “legitimated divorce for adultery,"[64] and indicates that divorce following porneia is not a sin[65] even though, as he says, it is a radical breach of the divine institution.

A historical approach would offer a less arbitrary analysis as well as probably more integrated conclusions. In the last analysis, the approach of Murray and Stott reflects a thoroughgoing legalism that focuses on texts rather than a broader perspectival approach to Scripture that recognizes the diversity of the biblical witness. Precisely at this point one finds the critical error of the dogmatic approach to exegesis. Ultimately, this “textual” approach ignores the diversity of the apostolic witness for the sake of uniformity.

By contrast, the historical approach is able to accept the multiple witness to Jesus as Messiah and to develop a better picture of primitive Christian faith. In this connection, we note that the second-century church, when faced by skeptics with the embarrassment of seeming contradictions and inconsistencies in the Gospel narratives, rejected out of hand the neat solution offered by Tatian’s Diatessaron. Instead, the Church preferred the fourfold witness with all its ambiguities, rather than accept any reduction in the apostolic witness. That diversity is still crucial, and the exegete as historian-rather than exegete as dogmatician-will be faithful to it.

Scripture is a product of history; it grew out of the history of God’s dealings with people. And the documents of Scripture reflect all the diversity of history. Evangelicals, of course, also believe they possess a fundamental and basic unity that reflects the all-encompassing purpose of God. The full scope of the biblical revelation comes to expression when we show an interest in this diversity equivalent to our concern for the unity in Scripture...

I dug up this excerpt on the subject of Jesus and divorce, taken from an article by Bob Lyon, who taught at Asbury until his death. It is in a volume titled, Interpreting God's Word for Today, published by Warner Press in 1982. Its contributors are Bible professors who taught at Wesleyan approved institutions at the time--and therefore while we do not have to agree with Dr. Lyon's train of thought, it stands within the parameters of Wesleyan thought.

I share it to give a sense of how many factors can go into making decisions on these sorts of things.

___________

AN EXAMPLE: THE DIVORCE ISSUE

One example might be given to show the illegitimacy of a nonhistorical approach. The issue of divorce-remarriage adultery is presented in Mark 10:llff.; Matthew 5:32, 19:9; and Luke 16:18. The main problem has to do with Matthew’s exception clauses. Both John Murray and John R. W. Stott resolve the issue dogmatically.[59] Both studies reveal a deep concern for Christian marriage as well as a thorough acquaintance with the background data. Yet both studies are ultimately unsatisfactory because they fail to ask certain necessary historical questions.

How did the varying forms of the saying(s) originate? Is one a derivative of another? Is there a merging of two originally separate topics (divorce and adultery)? Murray regards Matthew 19:9 as “the most pivotal passage” in the New Testament, not because it is the truly authentic (i.e., dominical) statement but because it is the most complete; that is, it has both the exception clause and the remarriage clause.[60] And Stott refers only to the form of the Pharisee’s question found in Matthew.[61] Both presume Mark and Matthew carry the same teaching; Mark omitted the exception clause because he assumed the exception.

But what about the community for whom Mark prepared his Gospel? Did it, or could it, assume an exception? According to Murray, the “silence” of Mark and Luke respecting the right to divorce does not itself prejudice the right to divorce. But are Mark and Luke silent? Did their communities believe they were silent? Do not both Mark and Luke give a rather clear word?

More important, neither Murray nor Stott asks the historical question, "What did Jesus say and how do we explain the various forms of the saying(s)?" From the four texts we come up with the following statements from the lips of Jesus:

(1) Remarriage following divorce constitutes adultery (Mark 10:11ff.; Luke 16:18);

(2) Except in a case of porneia, remarriage following divorce constitutes adultery (Matt. 19:9);

(3) Whoever marries a divorced woman commits adultery (Luke 16:18; Matt. 5:32);

(4) Whoever divorces his wife causes her to commit adultery.

Murray, whose treatment of the texts is much more extended that Stott’s, never asks if these are all separate sayings of Jesus or different versions of a single saying in response to the Pharisees. More important, perhaps, he does not treat the question whether the sayings have anything to do directly with the question the Pharisees asked. In this connection two observations are crucial:

(1) these sayings all relate to the question of adultery and not directly to divorce-that is, they answer the question of what constitutes adultery;

(2) except for Matthew 19:9, none of the sayings in their present context are spoken to the Pharisees who asked the question.

In terms of a historical-rather than dogmatic-approach, it seems Jesus answers the question of the Pharisees solely on the basis of Genesis 1 and 2, and that the various sayings derive from another context involving a discussion of the commandments. Whether they represent separate sayings or variant forms of a single saying is another matter deserving further study. The dogmatic approach fails methodologically because it begins by assuming Matthew and Mark say the same thing. One may come to that conclusion, but one cannot begin there.

Also, Mark and Luke are not, as Murray contends,[62] silent concerning any grounds for divorce. What they say would have to be considered by any common standards of literary analysis to be both clear and unequivocal. It is as arbitrary to interpret Mark and Luke on the basis of Matthew as the reverse. The evangelists must be heard and their community traditions recognized in their own right.

The problematic element in Murray’s study is seen in his variant conclusions. On the one hand, he rightly perceives that in the mind of Jesus, divorce “could not be contemplated otherwise than as a radical breach of the divine institution."[63] Yet elsewhere he says that Jesus “legitimated divorce for adultery,"[64] and indicates that divorce following porneia is not a sin[65] even though, as he says, it is a radical breach of the divine institution.

A historical approach would offer a less arbitrary analysis as well as probably more integrated conclusions. In the last analysis, the approach of Murray and Stott reflects a thoroughgoing legalism that focuses on texts rather than a broader perspectival approach to Scripture that recognizes the diversity of the biblical witness. Precisely at this point one finds the critical error of the dogmatic approach to exegesis. Ultimately, this “textual” approach ignores the diversity of the apostolic witness for the sake of uniformity.

By contrast, the historical approach is able to accept the multiple witness to Jesus as Messiah and to develop a better picture of primitive Christian faith. In this connection, we note that the second-century church, when faced by skeptics with the embarrassment of seeming contradictions and inconsistencies in the Gospel narratives, rejected out of hand the neat solution offered by Tatian’s Diatessaron. Instead, the Church preferred the fourfold witness with all its ambiguities, rather than accept any reduction in the apostolic witness. That diversity is still crucial, and the exegete as historian-rather than exegete as dogmatician-will be faithful to it.

Scripture is a product of history; it grew out of the history of God’s dealings with people. And the documents of Scripture reflect all the diversity of history. Evangelicals, of course, also believe they possess a fundamental and basic unity that reflects the all-encompassing purpose of God. The full scope of the biblical revelation comes to expression when we show an interest in this diversity equivalent to our concern for the unity in Scripture...

Augustine's On Christian Doctrine Book 3 (Part 1)

What follows is the first part of a summary and comment on this classic hermeneutical work by Augustine. If you want to read this classic Christian (and philosophical) piece, you will find it here.

__________

In Book 2 of On Christian Doctrine, produced in AD397, Augustine set out his understanding of how words indicate meaning. Words are "signs" that point to meanings. Ludwig Wittgenstein, a twentieth century philosopher, called this the "picture theory" of language. You might think of it like a cartoon. When I read a word, a picture that is the meaning for the word appears in the bubble above my head.

This only works some of the time. Wittgenstein pointed out that the meanings of a lot of words and "signs" can't be pictured. For example, you can picture a rude gesture but you can't picture its meaning. Other examples I might give include the word "is" or the word "righteousness." I personally do not even picture a "wild goose chase" and yet understand the phrase perfectly well all the same.

Wittgenstein much more soundly proposed that the meaning of words is not in some pictured definition but rather in the way we use them in certain contexts. In certain contexts or "forms of life," as he called them, we play certain "language games" with words. If I yell "fire" in a crowded room, you know that what I have really said is to leave the room as quickly as possible if you don't want to burn to death. If I yell "fire" as the commander of a group of men with rifles pointing at a blindfolded criminal, I'm probably telling you to shoot the person to death. More examples could be provided.

By the way, it is in Book 2 of Augustine's On Christian Doctrine that he gives what was no doubt becoming the consensus of Christians at that time concerning the books of the Old and New Testament. The canon of the Old Testament, as it is called, included the so called apocryphal books that Martin Luther would later remove from the Protestant canon. The canon of the New Testament corresponds to the list of books that had first appeared only three decades previously in the 367 Easter letter of Athanasius.

Book 3 deals with the question of Scripture's ambiguity and especially when we should read the Bible literally and when we should read the Bible figuratively. Some ambiguity can come from matters of punctuation (chap. 2). Here we need to keep in mind that texts of Augustine's day (and this was true of the original biblical texts as well) largely did not use punctuation to separate words from each other, let alone one sentence from another (it's called "continuous script," or scriptio continua in Latin). All the punctuation in our Bibles is a matter of interpretation.

Augustine of course teaches that decisions about punctuation should be guided by the "rule of faith" when one cannot resolve an issue on the basis of context. For the Christians of the earliest centuries, the rule of faith was that sense of basic Christian beliefs, core Christian thinking, the "deposit" of faith left by the earliest apostles. For Augustine, it was this basic Christian theology that resolved issues of ambiguity. We might put it this way: when in doubt, go with an interpretation that results in an "orthodox" meaning.

This approach brings out a crucial issue. It seems beyond question that the original meaning a biblical text had was a function of its historical and literary context. That is to say, the meaning a biblical author or a biblical audience would have understood by the words of a biblical text is a function of how words were being used at that point in time and place and that they would have understood the words of one verse in the light of the words that had come just previously.

What we will find repeatedly in Book 3 of On Christian Doctrine is that Augustine's decisions on the meaning of a text follow context unless that meaning bumps up against the rule of faith. In that case, he will shift into a figurative meaning that fits with the rule of faith and consider that the meaning God intends the text to have. He is by no means unique in this approach. We can easily find it in other interpreters of the time (e.g., the first century Jewish writer Philo), not least the New Testament authors themselves.

Since the Protestant Reformation, there has been reluctance to interpret biblical texts figuratively unless it was clear that the biblical authors themselves were being figurative originally. For example, we can interpret the story of Sarah and Hagar allegorically in Galatians 4 because that is the way Paul takes the story there. An allegory is where someone interprets the characters or various elements of a story as representations of something else that is unrelated to the original sense.

So Sarah in Paul's interpretation becomes a symbol of the heavenly Jerusalem, while Hagar symbolizes the earthly Jerusalem. This interpretation has nothing to do with the original story of Sarah and Hagar, which was about two women who fought over their children. Paul's interpretation is allegorical.

Evangelicals of the twentieth century have arguably tended to modify Augustine's approach. Follow what seems to be the most likely contextual meaning of the biblical text unless it comes into conflict with the rule of faith (that is, the "orthodoxies" of the evangelical tradition or the particular faith community of which one is a part). If they conflict, then find other possible ways to read the text in context such that it fits with the rule of faith. In this way, evangelical hermeneutics (the study of how to interpret texts) has avoided the kinds of non-literal interpretations of pre-Reformation interpretation while still trying to read the biblical texts in context. One of the purposes of this summary is to help us wrestle with these questions of hermeneutics.

Interestingly, Augustine considers some ambiguities of punctuation to be relatively unimportant. If context is not clear, if the rule of faith does not dictate a particular interpretation, he leaves it up to the individual. Punctuate however you like if neither the context nor the rule of faith give you a clear sense of how to punctuate...

The rest tomorrow

__________

In Book 2 of On Christian Doctrine, produced in AD397, Augustine set out his understanding of how words indicate meaning. Words are "signs" that point to meanings. Ludwig Wittgenstein, a twentieth century philosopher, called this the "picture theory" of language. You might think of it like a cartoon. When I read a word, a picture that is the meaning for the word appears in the bubble above my head.

This only works some of the time. Wittgenstein pointed out that the meanings of a lot of words and "signs" can't be pictured. For example, you can picture a rude gesture but you can't picture its meaning. Other examples I might give include the word "is" or the word "righteousness." I personally do not even picture a "wild goose chase" and yet understand the phrase perfectly well all the same.

Wittgenstein much more soundly proposed that the meaning of words is not in some pictured definition but rather in the way we use them in certain contexts. In certain contexts or "forms of life," as he called them, we play certain "language games" with words. If I yell "fire" in a crowded room, you know that what I have really said is to leave the room as quickly as possible if you don't want to burn to death. If I yell "fire" as the commander of a group of men with rifles pointing at a blindfolded criminal, I'm probably telling you to shoot the person to death. More examples could be provided.

By the way, it is in Book 2 of Augustine's On Christian Doctrine that he gives what was no doubt becoming the consensus of Christians at that time concerning the books of the Old and New Testament. The canon of the Old Testament, as it is called, included the so called apocryphal books that Martin Luther would later remove from the Protestant canon. The canon of the New Testament corresponds to the list of books that had first appeared only three decades previously in the 367 Easter letter of Athanasius.

Book 3 deals with the question of Scripture's ambiguity and especially when we should read the Bible literally and when we should read the Bible figuratively. Some ambiguity can come from matters of punctuation (chap. 2). Here we need to keep in mind that texts of Augustine's day (and this was true of the original biblical texts as well) largely did not use punctuation to separate words from each other, let alone one sentence from another (it's called "continuous script," or scriptio continua in Latin). All the punctuation in our Bibles is a matter of interpretation.

Augustine of course teaches that decisions about punctuation should be guided by the "rule of faith" when one cannot resolve an issue on the basis of context. For the Christians of the earliest centuries, the rule of faith was that sense of basic Christian beliefs, core Christian thinking, the "deposit" of faith left by the earliest apostles. For Augustine, it was this basic Christian theology that resolved issues of ambiguity. We might put it this way: when in doubt, go with an interpretation that results in an "orthodox" meaning.

This approach brings out a crucial issue. It seems beyond question that the original meaning a biblical text had was a function of its historical and literary context. That is to say, the meaning a biblical author or a biblical audience would have understood by the words of a biblical text is a function of how words were being used at that point in time and place and that they would have understood the words of one verse in the light of the words that had come just previously.

What we will find repeatedly in Book 3 of On Christian Doctrine is that Augustine's decisions on the meaning of a text follow context unless that meaning bumps up against the rule of faith. In that case, he will shift into a figurative meaning that fits with the rule of faith and consider that the meaning God intends the text to have. He is by no means unique in this approach. We can easily find it in other interpreters of the time (e.g., the first century Jewish writer Philo), not least the New Testament authors themselves.

Since the Protestant Reformation, there has been reluctance to interpret biblical texts figuratively unless it was clear that the biblical authors themselves were being figurative originally. For example, we can interpret the story of Sarah and Hagar allegorically in Galatians 4 because that is the way Paul takes the story there. An allegory is where someone interprets the characters or various elements of a story as representations of something else that is unrelated to the original sense.

So Sarah in Paul's interpretation becomes a symbol of the heavenly Jerusalem, while Hagar symbolizes the earthly Jerusalem. This interpretation has nothing to do with the original story of Sarah and Hagar, which was about two women who fought over their children. Paul's interpretation is allegorical.

Evangelicals of the twentieth century have arguably tended to modify Augustine's approach. Follow what seems to be the most likely contextual meaning of the biblical text unless it comes into conflict with the rule of faith (that is, the "orthodoxies" of the evangelical tradition or the particular faith community of which one is a part). If they conflict, then find other possible ways to read the text in context such that it fits with the rule of faith. In this way, evangelical hermeneutics (the study of how to interpret texts) has avoided the kinds of non-literal interpretations of pre-Reformation interpretation while still trying to read the biblical texts in context. One of the purposes of this summary is to help us wrestle with these questions of hermeneutics.

Interestingly, Augustine considers some ambiguities of punctuation to be relatively unimportant. If context is not clear, if the rule of faith does not dictate a particular interpretation, he leaves it up to the individual. Punctuate however you like if neither the context nor the rule of faith give you a clear sense of how to punctuate...

The rest tomorrow

Sunday, June 24, 2012

2.4 Implications of Textual Criticism

1. My early realizations about context

and continued with last weekend's start of discussing issues of the biblical text:

2.1 Issues of the Biblical Text

2.2 Manuscripts, Manuscripts

2.3 Common Sense Textual Criticism

Now the last of this group of reminiscences:

____________________

Those who wrote my church's statement on Scripture were careful to specify that they were talking about the "original manuscripts." In other words, they acknowledged the validity of textual criticism and legitimated modern translations for those who chose them. Stephen Paine, one of the primary influences on the Wesleyan Methodist's statements on Scripture, was actually involved in the translation of the original NIV.

There are theological implications here. If we accept the majority position, then the version of the New Testament that dominated Christianity from around 400 to 1950 was not exactly the same text as the ones the New Testament authors wrote. It was mostly the same to be sure, but perhaps as much as 5 percent different. The bottom line: God was not particularly concerned that Christians use the exact wording of the original texts. The message was what was important.

I might add that this is an implicitly fundamental value of Protestantism, implied by our fundamental sense that the Bible should be translated into the vernacular language. You can't translate the particulars of wording. Languages just don't do things the same way. So more than anything it is the message one translates.

Anyone who knows me will know my love of Greek and Hebrew and I am very interested in determining as much as possible the original wording of the Bible's books. But the implication here is that God does not require the original text in the original languages to speak through Scripture, indeed that it is not a priority for him at all. It implies that those who hate The Message because it is a paraphrase are out of touch with the way God has operated for the last 2000 years. It implies that those who have opposed the NIV2011 because of switches from singular to plural, to capture an originally intended inclusiveness, are misguided--sincere but misguided. It implies that it is not a high priority for God that we "get back" to the original wording in the first place.

It may also have implications at the very least for arguments over verbal versus conceptual inspiration. I don't think God has a problem with any word in either the original texts of the Bible or the Byzantine textual tradition. But it looks like God is really not so concerned with the precise wording. This at the very least tips the scales more toward "conceptual" rather than "verbal" inspiration. Conceptual inspiration is the idea that God breathed the fundamental message into the biblical authors and the precise words came more from them.

I'm not, by the way, saying that there may not be instances where God was very directive in the precise wording. Nor do I mean to preclude the possibility of some mysterious duality of both human and divine verbal inspiration. It is probably best for us not to pin it down.

It is distressing that people have faith crises over textual criticism and that people fight over which version of the Bible they use. Looking at the example of the biblical texts, God apparently was not worried about such things. In fact, when you consider that we are so limited in our end of understanding, so prone to see our own meaning in the words, it is quite absurd to stake our faith on minor details of wording.

and continued with last weekend's start of discussing issues of the biblical text:

2.1 Issues of the Biblical Text

2.2 Manuscripts, Manuscripts

2.3 Common Sense Textual Criticism

Now the last of this group of reminiscences:

____________________

Those who wrote my church's statement on Scripture were careful to specify that they were talking about the "original manuscripts." In other words, they acknowledged the validity of textual criticism and legitimated modern translations for those who chose them. Stephen Paine, one of the primary influences on the Wesleyan Methodist's statements on Scripture, was actually involved in the translation of the original NIV.

There are theological implications here. If we accept the majority position, then the version of the New Testament that dominated Christianity from around 400 to 1950 was not exactly the same text as the ones the New Testament authors wrote. It was mostly the same to be sure, but perhaps as much as 5 percent different. The bottom line: God was not particularly concerned that Christians use the exact wording of the original texts. The message was what was important.

I might add that this is an implicitly fundamental value of Protestantism, implied by our fundamental sense that the Bible should be translated into the vernacular language. You can't translate the particulars of wording. Languages just don't do things the same way. So more than anything it is the message one translates.

Anyone who knows me will know my love of Greek and Hebrew and I am very interested in determining as much as possible the original wording of the Bible's books. But the implication here is that God does not require the original text in the original languages to speak through Scripture, indeed that it is not a priority for him at all. It implies that those who hate The Message because it is a paraphrase are out of touch with the way God has operated for the last 2000 years. It implies that those who have opposed the NIV2011 because of switches from singular to plural, to capture an originally intended inclusiveness, are misguided--sincere but misguided. It implies that it is not a high priority for God that we "get back" to the original wording in the first place.

It may also have implications at the very least for arguments over verbal versus conceptual inspiration. I don't think God has a problem with any word in either the original texts of the Bible or the Byzantine textual tradition. But it looks like God is really not so concerned with the precise wording. This at the very least tips the scales more toward "conceptual" rather than "verbal" inspiration. Conceptual inspiration is the idea that God breathed the fundamental message into the biblical authors and the precise words came more from them.

I'm not, by the way, saying that there may not be instances where God was very directive in the precise wording. Nor do I mean to preclude the possibility of some mysterious duality of both human and divine verbal inspiration. It is probably best for us not to pin it down.

It is distressing that people have faith crises over textual criticism and that people fight over which version of the Bible they use. Looking at the example of the biblical texts, God apparently was not worried about such things. In fact, when you consider that we are so limited in our end of understanding, so prone to see our own meaning in the words, it is quite absurd to stake our faith on minor details of wording.

Saturday, June 23, 2012

2.3 Common Sense Textual Criticism

My weekend series of hermeneutical biography. It started with...

1. My early realizations about context...

and continued with last weekend's start of discussing issues of the biblical text:

2.1 Issues of the Biblical Text

2.2 Manuscripts, Manuscripts

We now join that show in progress...

___________________

In the end, it was not the so called "external evidence" of the manuscripts that convinced me to switch sides on matters of the biblical text. I was nowhere near knowledgeable enough to know whether the majority model about manuscript traditions was correct when I took the course in textual criticism at Asbury with Bob Lyon. I still don't know all the details. The consensus model is basically that at Alexandria, as especially embodied by manuscripts like Sinaiticus and Vaticanus and even earlier papyri, there was a fairly conservative copying tradition, the Alexandrian tradition. This is the most reliable manuscript tradition.

Then there is the Byzantine tradition, which generally corresponds to the Majority Text and what would become the Textus Receptus, the "received text" first put together when Erasmus first set the Greek New Testament to type. There was also the "Western" tradition of the Italic manuscripts and a few key Greek manuscripts like D, Codex Bezae. From time to time other textual traditions are also suggested.

This was all a fine story but I had no clue whether it was true or not when I went to seminary. I remember Dr. Lyon asking me after class once if I was a closet textus receptus guy. ;-) It made sense to me in general that an older manuscript was closer to the original than a later one. But in the end, it was common sense that prevailed. The basic rules of textual criticism, collected and perfected by Westcott and Hort, but originated in the years before them, made consummate sense. "Manuscripts must be weighed, not counted," because a thousand copies can be made of a bad manuscript.

Here's the mother of all rules: That reading is most likely to be original that best explains how the other variations would have arisen. There it is, so simple, so commonsensical. If one manuscript is missing a line other manuscripts have, and you can see that the same word would have been located about a line apart, then it's reasonable to assume that some copyist's eye skipped, from the end of one line to the end of the next, leaving out a line.

What this implies is that the "more difficult reading" is more likely to be original, because it is more likely that a copyist would smooth out roughness of some sort rather than mess it up. So, ironically, the Byzantine tradition is a smoother, more harmonized text than the Alexandrian. The majority of manuscripts at Colossians 1:14 read, "in whom we have redemption through his blood, the forgiveness of sins." The fact that modern translations omit the italicized phrase is no conspiracy, some lack of faith in the blood (after all, the blood is mentioned in 1:20). Rather, the earliest manuscripts lack the phrase and some scribe likely added it accidentally because he was thinking of Ephesians 1:7 where all manuscripts, including the earliest ones, have the phrase.

Conspiracy theories about modern translators are thus pure nonsense, based on ignorance of the manuscript situation. Disagree with textual scholars you may, but don't vilify them.

Let me use as an example the most famous of manuscript issues, the longer ending of Mark, Mark 16:9-20. The words of this text are attested early in some church fathers. However, it is not clear that those earliest church fathers were quoting Mark. They could have been drawing from something else. The earliest Greek manuscripts we have of Mark don't have these verses, and a couple key church fathers from the 300s and 400s indicate it was a minority reading at the time. The earliest manuscripts have nothing after 16:8 and there is another shorter ending in some manuscripts.

It was not the preceding paragraph that convinced me that 16:9-20 were not in the original. It was simply reading the flow. In Mark 16:1-8 the women, including Mary Magdalene, come to the tomb and find the stone rolled away. A young man appears to them, announces Jesus' resurrection, and instructs the women to go tell Peter to go to Galilee to meet him. But they don't. They tell know one because they were afraid...

And then it begins all over again: "Now after he had risen early on the first day of the week..." Now he is appearing to Mary Magdalene (with no mention of the earlier scene), who did you know he had cast seven demons out of? She goes and tells the disciples. Wait, what about the earlier statement that the women told no one? The verses that follow read like a summary of stories from other gospels (e.g., the men on the road to Emmaus from Luke 24 are in Mark 16:12. The Great Commission from Matthew 28 is in 16:15).

In short, Mark 16:9-20 know nothing about Mark 1:1-8. It reads like someone has inserted this summary of resurrection appearances from somewhere else. It is thus the "internal evidence" that convinced me that the vast majority of textual scholars were right on this issue. And it was the consistent alliance of the internal evidence with the textual traditions of the so called Alexandrian tradition that brought my secondary confidence in the prevailing sense of the external evidence. If you apply the commonsense model to the variations in the text, it consistently aligns with the manuscript tradition Westcott and Hort considered most reliable.

So in the case of Mark, the best explanation of the situation, in my opinion, is that the original ending of Mark was lost very, very early. It's possible Mark originally ended at 16:8 but I suspect there was originally more here. Two endings were added over time to try to make up for the abrupt sense of ending. The longer ending was taken from some early second century synopsis of the gospels, but a shorter one was created as well.

Since the longer ending is a more pleasing ending than an abrupt ending with the women telling no one, it was the reading that gained currency in worship and in copying. Thus the majority of manuscripts--mostly medieval since the older ones wore out--have the longer ending. But the older and more reliable ones don't. There's no conspiracy to take words out. There's no fiendishness to try to end the gospel on a dubious note. There is simply the following of the evidence to its most likely conclusion...

1. My early realizations about context...

and continued with last weekend's start of discussing issues of the biblical text:

2.1 Issues of the Biblical Text

2.2 Manuscripts, Manuscripts

We now join that show in progress...

___________________